July 28, 2012

First, I will start this post by quickly listing all of the things I will miss most about Japan:

- The food – Japanese food is awesome, no further explanation is needed

- The heated toilet seats and kotatsu tables (heated table with blankets) – they are awesome when it is cold

- The architecture - efficient houses, beautiful temples, sky-high pagodas, who wouldn’t miss it!?

- The Japanese gardens – they are so breathtaking, I cannot begin to explain how peaceful it is to relax inside of a Japanese garden

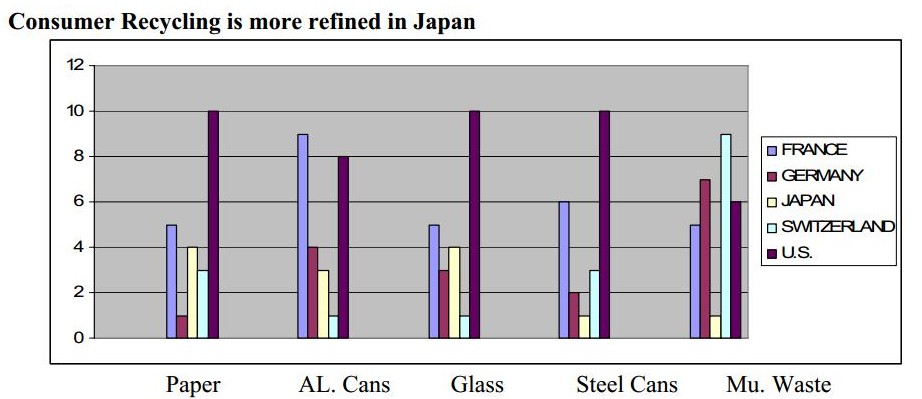

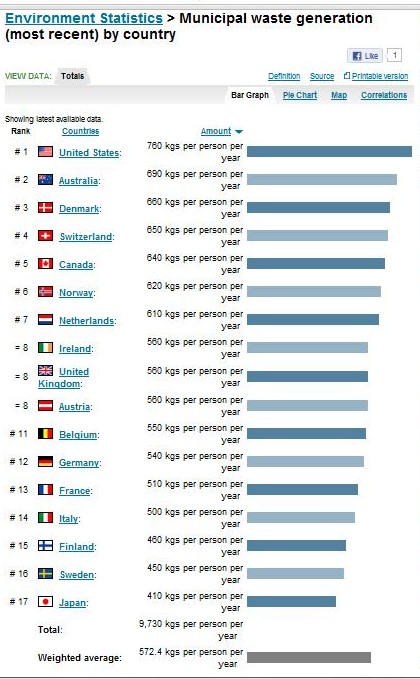

- The cleanliness – almost everywhere I go in Japan, the streets look very well kept and the streets are virtually trash free

- Japanese TV – I love anime, so that is obvious, but the game shows are so awesome! (even though it is still difficult for me to understand everything)

- The sense of safety – wherever I go in Japan, I always feel pretty safe, no matter what time of day or what area

- The public transportation – it is nice having practically ubiquitous trains, buses, subways that are almost always on time

- The people – everyone that I have met here has been so incredibly friendly and helpful; I can spout so many stories of how generous and helpful everyone here has been!

- The mindset – perhaps the thing I will miss most about Japan is the mindset of everyone. Being in Japan has exposed me to a new way of thinking that I really like. I think Japanese people have more of a general respect for everything including other people, the cities they live in, the environment, animals, etc